The Missing Half of Open Government

Paula Berman, Shu Yang Lin, John Griffin

July 1, 2025

Introduction

Over the last decade, Taiwan has gained widespread recognition as a pioneer in digital democracy. Using unique, technology-enhanced participatory methods, the nation has redefined global standards for several open government practices. Accounts in media and academia highlight the island’s unique accomplishments: from employing consensus-promoting algorithms to crowd-legislate[1]; to orchestrating hacktivist-driven civic collaborations[2]. However, so far these achievements have seen little replicability, especially across Western countries.

In this report we provide an English-language exposition of an element of Taiwan’s open government practices that so far has not held the same interest as some other case studies, as it doesn’t make use of any novel technologies. Instead, the Participation Officers Network (PO Network) is predicated on a simpler, yet powerful tool: conversations, or structured human interactions. Despite its seeming simplicity, we believe the PO Network to be fundamental to Taiwan’s exemplary execution of open government strategies. In sharing more details about its implementation, we hope to support others interested in transplanting some of Taiwan’s digital democracy practices to their own contexts and institutions.

Engaging representatives from 32 ministries, as well as a diverse array of private sector and civil society participants, the PO Network serves as a catalyst for tackling complex, multi-faceted challenges, with impressive agility. Since 2016 it has consistently turned citizen petitions, grievances and needs into substantial enhancements in public policies and government services. A prime example of this is its remarkable revamp of Taiwan’s complex tax filing system. After an e-petition was made by a citizen, claiming the platform to be “user-hostile,” the PO Network coordinated a series of collaborative, multi-stakeholder workshops to address the issue. Government officials were joined by ordinary citizens and UX designer specialists. Before the new tax year, a streamlined and user-friendly platform was launched—reducing the time it took to file taxes from hours, to mere minutes.

In the sections ahead, we’ll unpack the functioning of the Participation Officers Network and how it has evolved over time. However, we’ll begin by setting the stage with some context on open government’s theory and practice. In the realm of open government, much attention has been devoted to fostering communication between the government and its citizens. Here we bring to the forefront an equally vital but often underappreciated aspect: the internal communication within the government itself, spanning across its various agencies. In the model we describe, such communication channels are tasked with more than simply processing citizen demands; they facilitate their transformation into actionable, well-considered solutions. This transformation goes beyond a simple digital interaction; it entails continuous, productive dialogue with all stakeholders concerned with a particular issue—activist groups and private entities alike. Inspired by the work of legal scholar Yu-Tang Hsiao, we call this overlooked facet “The Missing Half of Open Government”: offering that both external and internal communication streams are equally vital for open policy-making processes.

The lessons of the PO Network illuminate a compelling approach for honoring the expertise of public servants; building resilient and responsive capacities into the large bureaucracies within which they conduct their work; and for tackling complex, multi-faceted challenges that involve a plurality of stakeholders. In an age of networked challenges, the capacity for having dynamic and substantive collaborations across a diverse range of public, private and civil society actors is increasingly needed. As we’ll detail in this report, Taiwan’s PO Network offers one insightful example of the kind of infrastructure that can be employed to facilitate such collaborations.

Acknowledgments

This case study is inspired by Yu-Tang Hsiao’s thesis, “The Missing Half of Open Government”, submitted in 2021 to the Stanford Program in International Legal Studies at the Stanford Law School; as well as the work of co-author Shu Yang Lin, a co-Founder of the Public Digital Innovation Space (PDIS) in Taiwan.

Part I: The Missing Half of Open Government

Open government is a governance concept that promotes principles of transparency, accountability, and citizen participation in government action. As a practice, many trace its origins to former U.S. President Barack Obama’s “Open Government Initiative”, which began on his first day in office, January 20th, 2009, with a directive calling for leveraging new technologies to promote transparency in government, fight corruption and bring civic participation into decision-making processes. Today, the Open Government Partnership, a derivative of the Open Government Initiative, is an established and growing movement supporting governments around the world in their commitments to openness—with 76 countries and 106 local governments as active participants.[3]

In theoretical terms, the current literature on open government bifurcates into openness in informational terms and openness in interactive terms.[4] The information aspect revolves around freedom of information, active dissemination of information, access to documentation, usability of websites, and access to information. Meanwhile, the interactive aspect centers around interactive policy-making, consultations, communications, and stakeholder involvement.

While the informational aspect of open government dominates the relevant literature and practice, investigation and experiments on the interactive dimension of open government have been relatively scarce.[5] Furthermore, within the comparatively smaller niche of interactive policy making, little attention has been paid to the interactive aspect of open government between government agencies.[6] Instead, the interactive aspect is commonly depicted as interaction between “citizens” and “government”.

While some attention in the open government field is paid to cohering citizen demands through various deliberation practices, governments themselves are treated as monoliths. This neglects that governments are also living and plural organisms, that comprise tens or hundreds of thousands of civil servants. Public officials are not simply cogs in a machine, but distinctive individuals, working under distinctive agencies, with distinctive missions. Therefore, we offer that considering how to engage and cohere this multitude of needs and perspectives is key to the effectiveness of open policy-making processes. Yet, when it comes to e-government, few consider intra-governmental relationships and networks.

This neglect may have important implications. Despite initial optimism that new technologies could enhance interaction between citizens and governments, digital democracy initiatives in the West have often fallen short of translating into substantial policy enhancements. These shortcomings result in a two-fold frustration. Citizens, on one hand, feel their voices are overlooked, while public officials often perceive citizen inputs as unrealistic, and operating under ill-informed assumptions (such as overestimating public budgetary capabilities.)

These issues may not stem from an inherent lack of good judgment from citizens, but the inevitable asymmetry in knowledge about the context and constraints that shape daily policy-making decisions for public officials. If so, the answer is not to have less citizen engagement, but more: richer interactions with comprehensive exchanges of information. Many digital democracy initiatives are too narrow in their scope, offering only a limited set of questions and answers, rather than fostering a substantive dialogue. Left out of their design are contextually rich, collaborative exchanges between different stakeholders that could mitigate the information disparities between them, and lead to constructive citizen engagement.

Sortition-based citizen assemblies present a stark contrast to simplistic digital democracy. Traditionally, these assemblies immerse participants in thorough learning processes, featuring presentations and discussions involving key stakeholders concerned with a particular issue. A standout example is the Paris Citizen Assembly. As one of the first conventions of its kind to be institutionalized as a permanent entity, in April 2023 it finalized its recommendations for end-of-life practices, with participants reaching a high degree of consensus.[7] This and other accomplishments helped solidify the model as a credible and legitimate avenue for deliberation, especially on highly polarizing political matters.[8]

The infrastructure we discuss in this report embeds some of the deliberative and collaborative practices exemplified by citizen assemblies, integrating them directly into the fabric of traditional—and often inaccessible and bureaucratic—institutions. Existing precedents suggest that the PO Network model could be particularly effective in handling issues that aren’t heavily disputed, and / or do not have a clear, single “owner” (i.e. involve multiple stakeholders). For example, the use cases we detail include redesigning Taiwan’s tax-filing system, implementing a plastic straw ban, and developing a nationwide, unified system for hiking permits.

A helpful analogy might be to consider sortition-driven processes as the major arteries, channeling citizen participation into decisions that involve core social issues, with significant value trade-offs and therefore requiring a high degree of legitimacy. In contrast, the PO Network model could be seen as a helpful way to reach the smaller vessels, infusing the farthest reaches of public administration with well informed and productive inputs from citizens.

The PO Network model aims at this objective through two primary mechanisms. First, a unique role has been introduced for civil servants: Participation Officers. These officers are entrusted with the task of conversing with a wide array of stakeholders, understanding their interests and facilitating a goal-oriented cooperation between them. Second, a specialized network for these officers, known as the PO Network, facilitates efficient collaboration between government agencies throughout the different open policy-making processes they engage in. This ensures that all pertinent departments and stakeholders can have a seat at the table, and can voice their needs and concerns.

Part II: From Open Source Culture to Open Government Policies

Before diving into a detailed description of the PO Network model, in this section we briefly describe the political context that led to its emergence. In the early 2010s, Taiwan saw a rise in civic engagement with numerous political protests and social movements. Citizens were increasingly dissatisfied with their government, and this came to a head on March 18, 2014. Students and civic groups took over Taiwan’s Congress building to protest the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement (CSSTA) with China, on the grounds that it was examined without sufficient transparency and consultation with civil society, and could leave Taiwan too vulnerable to Chinese influence. Activists claimed that their voices were not heard in this critical agreement, and that the policy-making process was a black box.[9] The occupation lasted 24 days, attracting thousands to the streets, who joined in singing “Do You Hear the People Sing” from Les Misérables, waved banners, and carried sunflowers as symbols of their cause. As such, this became known as the Sunflower Movement, and it was the largest nonpartisan, pro-democracy rally in Taiwan’s history.[10]

A significant portion of the protesters were digital natives—millennials and raised with the Internet—who brought open-source culture into their social movements. Among them were open source communities and civic groups such as g0v, one of the most computer-savvy political communities in Taiwan; and one of its most well-known participants, Audrey Tang (Audrey would go on to become Taiwan’s first Minister of Digital Affairs). At the outset of the occupation, Tang used Ethernet cables to connect the occupiers inside the Congress building to the Internet and broadcast the discussions being held inside. g0v also provided a forked version of the Congress’s website (which during the occupation had more visits than the official version), in addition to collaborative multimedia workspaces for multilingual announcement and meeting transcripts.

By incorporating civic and open-source technologies, netizens and young generations came onto the political scene, creating a new space to engage in public discourse. But they also captivated and broadened the imaginations of Taiwanese society at large, which began advocating for open government.[11] In response, the Executive Yuan—the top executive branch of the central government in Taiwan—convened a series of citizens constitutional conferences in the summer of 2014 to reach agreements with citizens on public governance. One of the agreements stated that the government should build an online platform to allow for regular civic participation, establish procedures for filing e-petitions, and provide access to policy-related information. This agreement acted as a basis for establishing mechanisms for civic engagement in an open policy-making process.

Following the convening, the Executive Yuan directed Taiwan’s National Development Council (NDC) to construct an online platform for ongoing civic participation, and to create procedures for filing e-petitions. The NDC launched the JOIN E-petition Platform (JOIN Platform) on February 10, 2015. However, the JOIN Platform is different from other usual e-petition platforms to the extent that it became connected to a sophisticated open policy-making process that provides petitioners, stakeholders, and public officials with a collaborative space.

We call this full process the “Participation Officer Network Model”(PO Network Model). The design of the full model and its various components was provided by the Public Digital Innovation Space (PDIS),[12] a new policy lab established inside the Executive Yuan. The decision to move from a simple e-petition platform (with ad-hoc government teams assembled to respond to each successful petition), to the more comprehensive PO Network model came about due to several coordination inefficiencies that were identified in the early stages of JOIN’s implementation.

A publicly available discussion between Audrey Tang — a member of g0v who was invited to join the government as Digital Minister Without Portfolio — and Pang Guocai, Director of Asset Management at NDC illuminates some of those challenges:[13]

-

Fragmented Expertise: Citizen engagement work within the government space requires different types of expertise, including facilitation expertise (conducting online and offline discussions that foster empathy and elicit initial consensus), recording expertise (documenting conversations through text, video, or audio, such as transcribing or livestreaming), and translation expertise (bridging communication between government and citizens, and among various government agencies through data analysis, clear language and scenarios depiction). Within the NDC, these functions were dispersed across different government units, making it challenging to effectively coordinate a cohesive workforce when addressing petitions and ensuring comprehensive coverage of skill sets.

-

Lack of Continuity: Within the initial protocol for handling petitions, it was rare to see continuity among the individuals in charge of them. The turnover of personnel and responsibilities between different workshops and consultation sessions resulted in low consistency and continuity. This hindered the ability to leverage past decisions and learning experiences.

-

Limited Availability: Many staff members had only a fraction of their time available to manage citizen engagement tasks, making it difficult to oversee the diverse range of responsibilities. On the other hand, creating new position openings proved unfeasible due to resource constraints.

-

ross-Ministry Coordination: Many petitions require data, response, and action from more than one ministry. The initial framework of JOIN did not explicitly accommodate for inter-ministerial coordination. However, when tackling intricate challenges, different ministries were in need of a shared platform to facilitate collaboration, especially for endeavors that were previously non-existent.

-

Personnel Constraints: The existing structure didn’t allow for the creation of additional offices or teams within the NDC, given ongoing reorganization efforts, and hence a new approach was needed.

These are common challenges and constraints in the field of open policy-making processes. Yet, the ingenuity of the PO Network Model is its relatively lightweight implementation requirements. No new public servants were hired, and tasks were divided across an extended network to make their execution feasible. By dint of being connected to other public servants through the network, motivated Participation Officers had a favorable environment to share their learnings, exchange valuable insights, and mutually support each other during challenging moments.

Part III: The Participation Officer Network Model

The Participation Officer Network Model entails three key elements, described in detail below:

(i) JOIN’s e-petition Platform;

(ii) an interagency network of Participation Officers;

(iii) the multi-stakeholder Collaborative Workshop, held on an as-needed basis.

The PO Network Model

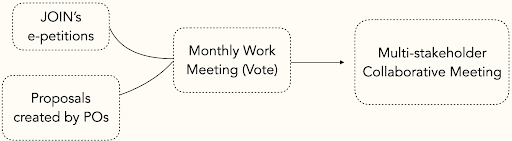

The JOIN Platform supplies the e-petitions that serve as the primary input for policy-making. To be considered for selection the e-petitions must have gathered more than 5,000 signatures within 60 days. Additionally, POs are also invited to propose their own petitions, within the scope of their own agency’s mission.

At the start of each month, POs from the NDC alongside members of PDIS, select potential e-petitions from the JOIN Platform. These are then brought to the Monthly Work Meeting for voting. All POs can vote for the e-petitions they believe are suitable for a collaborative workshop. On average, three to four e-petitions will be selected through this process. The proposals that gain the most votes will be discussed in the collaborative workshop, which are led by POs, and harness design thinking methodologies and open-source tools for co-creating solutions.

I. The JOIN Platform

The JOIN Platform features five online public services, including policy consultation, project supervision, participatory budgeting, a portal for “emailing a minister,” and a system for e-petitions. For the purposes of this case study, in this segment we focus on the e-petition service.

The service enables all citizens to file and/or sign e-petitions. The signers can express their opinions when adding their signatures. If an e-petition gathers more than 5,000 signatures within 60 days, the government agency which holds executive authority regarding the subject matter of the e-petition must respond within 2 months. Most e-petitions demand reforms for policies, regulations, or laws.

After six years of operation, the JOIN Platform became one of the main channels through which citizens deliberate over public matters in Taiwan. According to Taiwan’s National Development Council (NDC), the number of e-petitions it received between the years 2015 to 2020 in total is 9,228 and the number of those which successfully passed the threshold of the 5,000 signatures within 60 days in total is 210.[14]

Moreover, according to an online survey conducted by NDC in 2020, citizens aged between 20 to 49 years old accounted for the majority of the active users on the JOIN Platform (82.6 percent). 75.6 percent of the users had attained at least a bachelor’s degree, and 78.3 percent of the users lived in the urban areas. These findings indicate that the platform is more popular among the younger generation and educated, urban communities. This suggests a digital divide between generations and the urban-rural income gaps. Thus, one should bear in mind that the analysis on the JOIN Platform does not represent the whole population in Taiwan. Rather, it illustrates the trend that the younger generation tends to discuss public matters on the Internet.

II. The Participation Officer Network

Participation Officers steward the open policy-making process across the JOIN platform, monthly work meetings, and collaborative workshops. This new role was created amid a particular context: In contrast with citizens’ vibrant communications on social networks, public officials often face challenges in communicating with each other, both within their own agencies and across multiple agencies. That is because public officials’ behaviors are constrained by the position they hold and the agency they work for. However, activists and civil society are usually not familiar with the government’s internal communication systems and the relevant norms and constraints under which they operate. To help address the challenge, then Minister Without Portfolio Audrey Tang and their colleagues at the Public Digital Innovation Space (PDIS), conceived of a new role for public servants, named “Participation Officers”.

POs were trained and supported to act as highly sophisticated communicators and collaboration facilitators, tasked with bridging the gap between citizens and their e-petitions with public officers on one hand, and across public officers, on the other. This new role drew inspiration from the existing practice of having liaison officers for legislative activities. Similarly, by establishing a network of liaison officers public officials can be kept informed about external developments and encouraged to maintain dialogue with society. One of the PDIS members, Ning Yeh, pointed to this network, saying:

“For legislative activities, we have liaison officers, but for public governance, we do not have a similar channel to keep our public officials informed of what’s happening out there. [But] Public officials [also] need to interact with each other and make conversation with citizens.”

Following the proposal, Premier Chuan Lin approved the idea in November 2016 and mandated each government agency to appoint at least one PO.

In addition to drawing inspiration from legislative liaison officers, the Participation Officer Network was also amplifying an existing sentiment already resonating online. In particular, a post was made on a popular online forum in Taiwan, rallying civil servants to act as “participation agents”, and was met with numerous responses from civil servants expressing their readiness to volunteer. This shows how the PO Network itself began with an element of bottom-up, decentralized and informal coordination at its origins. Audrey Tang and her colleagues at PDIS helped institutionalize it, but this element of open source culture would become key to the ethos of POs.

As the network was officially approved and PDIS began structuring the network, this open source ethos was largely manifested through two steps: Identifying existing change-makers, and then empowering them to take action.

-

Identifying change-makers: To support the long-term sustainability of the effort, PDIS members agreed that the change had to be initiated from within the government. Therefore, instead of hiring external, contracted consultants, the initiative began by identifying and recruiting civil servants who were already breaking silos between ministries and functions, in their individual capacity.

-

Empowering change-makers: To best empower these change-makers PDIS positioned itself as the supporting organization, working closely with POs and providing resources to support their initiatives. PDIS emphasized it would act as the “servant of public servants” and give them full power to act on behalf of PDIS if necessary. Additionally, participatory design and open source communities were called in to train POs and support their activities, equipping them with sophisticated design thinking techniques and the ability to have high standards of transparency in their work. g0v members also brought in their expertise,broadcasting and transcribing the Collaborative Workshops, to make them publicly accessible (in the same way that open source collaborations take place publicly through platforms like Github). These contributions from various communities equipped POs to become experts at gathering various stakeholders, and transparently fostering collective dialogue between them to address and devise solutions for policy dilemmas.

One more important expression of this decentralized ethos is the offering for POs to also submit ideas coming from their teams or themselves, to be worked on by the PO network. In other words, public servants’ needs were elevated and given space, side-by-side with citizen-led petitions. Therefore, the model can respond to pre-existing incentives within government, simultaneously empowering both citizens and public servants. This is in stark contrast to most citizen engagement initiatives or reforms, which are strictly aimed at elevating citizen demands — therefore neglecting the importance of public servant expertise.

After recruiting and onboarding POs from across 32 ministries, a specialized network was created for them to coordinate around new policies. The PO Network is marked by three routine meetings:

-

Quarterly Facilitation Meeting: This meeting invites the Vice Minister and the Chief Information Officer from each agency to deliberate over their main policies and action plans related to open government.

-

Monthly Work Meeting: All POs attend this meeting, proposing and voting on policies and e-petitions suitable for collaboration.

-

Collaborative Workshop: This gathering is held as needed (often twice a month) and discusses the e-petitions and policies selected in the monthly work meeting.

III. Collaborative Workshop

One of the major events of the PO Network is the collaborative workshop. This is the main arena in which public officials and citizens intensively collaborate with each other in the open policy-making process. It serves as a one-day facilitated workshop involving POs, non-PO public officials, petitioners, and other key stakeholders to brainstorm a subject at issue, such as a law, regulation, or policy, through a design thinking process. The workshops often take place in a medium-sized meeting room within the ministry’s office building, having participants present in turns in the first half of the day, then smaller group discussions after a lunch break.

The collaborative meeting allows for open dialogue and shared decision-making, fostering a relationship of trust and mutual understanding between the public, the officials, and any other relevant stakeholders. This format encourages the diverse range of attendees to brainstorm, discuss, and potentially resolve the policy-related issue at hand in a concentrated, efficient manner.

Participation Officers (POs) play a crucial role in the process: they are tasked with serving as network weavers, establishing conducive threads of communication between a wide variety of stakeholders such as PDIS, petitioners, stakeholders, and public officials from different government agencies. With a few procedural norms in place, such as having a broadcast team streaming their collaborative meetings so that those are available for public scrutiny—and therefore mitigating concerns about undue influence—they are able to foster rich collaborative efforts with a wide variety of actors.

Between the launch of JOIN in February 2015, and December 2020, 80 collaborative meetings were convened. The organization of a one-day workshop can take one to three months of preparation, and encompasses a series of tasks. This preparation period is key to ensure that the workshop is well-structured, relevant, and valuable for all attendees. Here are some of the steps and roles habitually taken by POs, throughout the process:

-

Conducting interviews: POs communicate with petitioners to understand the essence of their concerns and ensure that those are correctly represented during the discussion. Additionally, they gather a range of perspectives and information from other key stakeholders, gaining an in-depth understanding of their views, concerns, and suggestions regarding the policy in question.

-

Performing research: This involves looking into the existing literature, data, and information related to the policy. It provides a solid factual basis for the discussions during the workshop.

-

Holding preliminary meetings: These meetings are often conducted to discuss early findings from the interviews and research, and plan the format and agenda of the workshop. These meetings sometimes involve external stakeholders or other ministry’s PO depending on the responsible PO’s leadership. Because the open policy-making process is still new to many of the participants, these meetings also provide an opportunity to offer a clear explanation to all of the different stakeholders about how the collaborative meetings work, setting expectations and reducing potential confusion or misunderstandings.

-

Structuring the facilitation process: POs are involved in designing the format of the collaborative meeting, ensuring that it is well-organized and conducive for meaningful discussion and problem-solving.

-

Project tracking: This ensures that the workshop’s preparation is progressing as per schedule and all necessary tasks are being completed. After the collaborative meeting, some POs will keep track of the government agency’s response to the e-petitions and also serve as project supervisors or project managers to improve the productivity of the open policy-making process and ensure results are delivered in a timely manner.

We note that the role of a Participation Officer involves great responsibility: POs often serve as representatives on behalf of their own government agencies on the JOIN Platform and as a contact point for the petitioners. They may need to stand in the front lines with other public officials who are also responsible for the given subject in their own government agency, to directly face the petitioners.

Another way to frame this role is that POs are highly sophisticated communication agents. Empowered with open source technologies, procedural rules based on transparency, and design thinking processes, they act as a bridge between the Executive Yuan, government agencies, citizens, activist groups and private actors, in the open policy-making process.

To provide a sense of the tools utilized, below we outline a short selection of the methodologies POs are trained in and implement in the Collaborative Workshops:

-

ORID:[15] This methodology makes use of strategic questioning, (Objective, Reflective, Interpretive, and Decisional questions) to structure facilitated dialogues. In exploring the objective facts, subjective feelings, thoughts and decisions regarding a particular subject, participants are naturally stewarded to reach a consensus. When facing complex topics, this approach is often used to construct conversations that help participants discuss and focus on key issues.

-

Persona: Personas are personal images of fictional realities that describe a particular group of subjects. By drawing the behaviors, actions, and preferences of single personalized characters, groups can be better understood. Such role-playing helps ensure that work is always focused on the user, not an abstract description of their respective groups.

-

User Journey:[16] User Journey is the process of showing how people interact with services step-by-step. Through the user experience journey, the work team can identify problem points in the service process to confirm which parts of the new ideas can be improved.

-

Idea Development Sheet: Idea Development Sheet is a canvas tool[17] inspired by Policy Lab and then further developed by PDIS used in collaborative meetings. It is a quick tool to help stakeholders around the table understand issues at hands, sketch out a quick idea and plan the next steps.

-

Transcript: Transcript is verbatim notes that records all speeches in the meeting as fully as possible. Through a transcript, all interested parties—even those not present in the physical room—will be able to understand the full course of the day’s discussion after the meeting. At the same time, you can see how different stakeholders address each other’s needs in the meeting. In addition to allowing participants to understand the context of the discussion, open online verbatim text can also reduce future repeated discussions on the same topic; A verbatim presentation can also serve as a basis for post examination to avoid the participants being misinterpreted as necessarily supporting the conclusions of the meeting.

-

Live broadcasting: Live broadcast is a more comprehensive, instant recording than verbatim. Through public audio and video, people interested in the issue can immediately participate in the meeting, understand the status of the discussions, and immediately share their views, so that more interested friends can join the meeting immediately. The live video left on the Internet after the meeting can also be used to restore the meeting process and present the material of the discussion, although it takes some time to watch. Notably, the live broadcast may give some attendees a “show” incentive to influence the meeting.

-

Sli.do: Sli.do is a meeting supporting tool. It allows participants to leave anonymous messages to help people who are not able to speak in public to voice their ideas; through an anonymous liking mechanism, it can also help people focus on issues that are important to others and help bring the issues together. A paid version of Sli.do also allows for discussion or voting at meetings.

-

Polis: Pol.is is an online opinion collection tool through which the public can put forward their own views and comment on other people’s views. Pol.is mainly uses algorithms to group people’s opinions. It allows the convenience of visualizing several groups of different opinions on the Internet, as well as mutually agreed views, which can be further used as a reference for agenda setting.

-

Quadratic Voting: Quadratic Voting (QV) is a collective decision-making method that allows people to express not just what they want, but how strongly they feel about it. Participants are given a fixed number of credits to allocate across different options, with the cost of each additional vote increasing quadratically (e.g., 1 vote costs 1 credit, 2 votes cost 4 credits, 3 votes cost 9 credits). This makes it more costly to heavily support a single option, encouraging people to carefully weigh their preferences. QV is especially useful in surfacing shared priorities and mitigating majority domination, offering a more nuanced picture of group sentiment that can guide fairer and more informed decisions.

Part IV: Case Studies

Case Study 1 | Tax Reporting System Redesign - 2017 #CM007

During the 2017 tax season, a UX designer highlighted the inefficiencies of the current tax reporting system with an e-petition stating, "We have an explosively user-hostile tax reporting system.” The PO from the Ministry of Finance presented this concern at a monthly meeting, sparking an initiative to enhance the online tax reporting experience.

The initial tax filing interface was antiquated, laden with jargon, and users frequently discovered additional document requirements only midway through the reporting process. These issues were pinpointed in the inaugural collaboration workshop, leading to three subsequent workshops over the next four months. A diverse group of stakeholders— users, IT contractors, government officials, and designers—attended these sessions. Together, they crafted prototypes using paper-cut components. Design and engineering communities transformed these into interactive prototypes. The final design was then passed to the contractor responsible for revamping Taiwan’s tax filing system.

Launched just before the tax season in 2018, the overhauled system showcased a significantly improved user experience. The intuitive interface enabled users to complete their tax reporting much more rapidly. Users commented that they could finish tax reporting in an enormously shorter time frame. “Even within a cup of bubble tea’s time.”, commented one of the users. According to a polling[18] from Trade-van Info Services, 77% of the online tax reporters now finish their tax reporting process within 20 minutes.

Case Study 2 | Plastic straws ban - 2017 #CM013

In summer 2017, a popular petition to ban single-use utensils raised above the 5000 signatures threshold and later on passed the monthly vote among Participation Officers. The Environmental Protection Agency and the Ministry of Economy Affairs set out to prepare for the collaborative workshop. While reaching out to stakeholders they realized that the petitioner was a 16-year-old student who created the petition as part of her civics class assignment.

A diverse group of stakeholders was invited, including public officials from the Environmental Protection Agency, environmental activists, street food shop owners, homemakers, and more. Among them, single-use utensil manufacturers also participated and added their perspectives. Utensil makers explained that they entered the businesses to produce single-use utensils when hepatitis B was prevalent in Taiwan. They made those single-use utensils to safeguard public health from the virus. As hepatitis B became less of a threat to public health, they were also looking for new materials. The afternoon session became a brainstorming workshop to find new materials for manufacturing straws. Nowadays in Taiwan, you can find not only paper straws but also straws made of sugarcane waste that is zero or negative carbon in its carbon capturing. The Environmental Protection Agency and the Ministry of Economy Affairs were aligned with the direction and committed to work together on rolling out a gradual ban.

On 8th June 2018, the Environment of Protection Agency formally announced the draft policy restricting the use of disposal plastic straws. Starting from July 2019, a total of 8,000 businesses, including government agencies, public and private schools, department stores, shopping centers, and chain fast-food restaurants, were prohibited from providing dine-in customers with single-use plastic straws. As a result, an estimated 100 million straws were removed from circulation annually.[19]

Case Study 3 | Integrating Mountaineering System - 2019 #CM045

Our final case study illustrates the fulfillment of a demand that was introduced from within government. There are more than 200 distinct peaks over 3,000 meters in height in Taiwan. For most of them, hikers would need to apply for an entry permit and be approved before going on the hike. The application services were scattered over different pages, as paperwork could be designed independently by different administrations, making it a hassle for mountain hikers. In early August 2019, the Ministry of the Interior, the governing body for Mountaineering in Taiwan, proposed at the Participation Officers’ monthly meeting that the case be brought forward for collaboration, for a better hiking permit application experience.

Relevant stakeholders were invited to participate in a collaborative workshop. Additionally, a digital survey tool, Pol.is, was used to gather wider opinions across the Internet. It became apparent that an integrated system for mountain climbing applications was needed. PDIS involved student interns in building mockups and testing them. With limited resources, the final solution called for RESTful API (Open API Specification 3.0), commissioning original IT system makers to build an API, and another contractor to build an integrated system.

Conclusion

For almost a decade, Taiwan has captivated the attention of open government supporters for its digital culture and its novel use of technological tools for public policy ends. In Western countries like the United States, that attention has largely centered around a few digital innovations employed by Taipei. The best-known is almost certainly Pol.is, a platform that the Taiwanese government uses to gather and process public opinion, identifying key trends and hidden consensus on issues in the public sphere. As evidenced by the numerous podcasts, articles, and conference talks taking place in the US, American observers are eager to learn from Taiwan’s use of technology to bolster democracy.

Technology, though, is only part of Taiwan’s open government story—albeit an important one. Equally important is the human element undergirding the island’s use of digital tools. As this case study has argued, Taiwan’s Participation Officer (PO) Network plays this crucial role, gathering public opinion data and creating deliberative contexts for policy development. Digital tools produce the information needed for open governance, while the PO Network helps both the public and the government to craft effective policy from this information. It is a cross-ministry deliberately designed for communication and of mutual visibility, allowing everyone involved in a given question to see the facts and implications at play, and thereby to shape together the policies impacting their own lives and livelihoods.

But perhaps the distinction between technologies and human-led methodologies is overdrawn: the PO Network Model we describe follows the same historical line of other networked approaches to organizing, such as Wikipedia. Each of the case studies we present shows this integration, with the PO Network playing a complementary role in ensuring full visibility and co-creation opportunities for all stakeholders, within a digitally-informed policy development process. In the tax reporting case, for instance, the initial impetus for reform came from one of Taiwan’s digital democracy tools, the e-petition platform. With its cross-ministry presence and connections to the public, the PO Network was uniquely situated to assemble the right group of stakeholders to design, test, and implement a new system. Similarly, when the e-petition system identified a desire to limit single-use utensils, the PO Network was able to curate a deliberative discussion among environmentalists, industry representatives, and members of the public, highlighting unforeseen concerns and crafting a better policy response. With the mountaineering system example, the original call for action came from within the government itself—the Ministry of the Interior—and the PO Network then used both Pol.is and a collaborative meeting to find an open-source solution. In each case, inputs from digital tools were necessary for the policy development, but equally necessary was the PO Network’s weaving those inputs into a human-mediated, contextually-rich deliberative process.

These examples also show that successful open government initiatives must respond to two separate but interlocking sets of incentives:

-

The incentives driving citizens to participate in the process. For open government to work, there must be ample information flow between citizens and the government. Citizens need to have access to the platforms used to gather their opinions, it must be easy and rewarding to use those tools, and they should be able to see how their participation drives policy change. In the mountaineering example, for instance, the PO Network relied on strong public use of the Pol.is platform to collect public opinion information about possible solutions. If the public did not participate, there would be insufficient information for the PO Network to construct a deliberative process.

-

The incentives driving government officials to engage and direct their efforts toward open channels, rather than internal ones closed off to the public or even other parts of the government. An open government initiative will be much more likely to see success if it makes officials’ jobs easier and more fulfilling. As in the plastic straw example, open channels between multiple government entities—like the EPA and Ministry of Economy Affairs—can make the difference in crafting a winning solution. Open government requires that officials feel comfortable working across these agency lines. Communication must be strong and free not just between government and citizens, but also within the government itself.

This second set of incentives has received less attention in popular accounts than those addressing government-citizen information flows, perhaps because digital and scalable technology played a larger role in the latter. Yet the networked methodology of the PO Network is itself a technology we should pay close attention to. With its thoughtful, human-centered design, it allows novel tools to be embedded within a comprehensive public infrastructure.

As international observers look to replicate Taiwan’s open government successes, they would do well to implement not only digital tools like those used on the island, but also the networked institutional approach required to harness these tools to their fullest potential. The logic behind should make intuitive sense: apply the value of seeing and shaping one’s policy environment to public servants themselves, and together with citizens they can bring about real transformation.

Notes

Andrew Leonard, “How Taiwan’s Unlikely Digital Minister Hacked the Pandemic”, Wired, July 23, 2020, https://www.wired.com/story/how-taiwans-unlikely-digital-minister-hacked-the-pandemic/. ↩︎

Jaron Lanier and E. Glen Weyl, “How Civic Technology Can Help Stop a Pandemic”, Foreign Affairs, March 20, 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/asia/2020-03-20/how-civic-technology-can-help-stop-pandemic. ↩︎

Open Government Partnership, “About,” Open Government Partnership, accessed Jan 23, 2024, https://www.opengovpartnership.org/about/. ↩︎

Albert J. Meijer et al., “Open Government: Connecting Vision and Voice,” International Review of Administrative Sciences 78, no. 1 (2012): 10-11. ↩︎

Brian Reich, “Citizens’ View of Open Government,” in Open Government: Collaboration, Transparency, and Participation in Practice, ed. Daniel Lathrop and Laurel Ruma (2010), 131-138. Reich emphasizes that the concept of open government and the release of government data often overshadow discussions about their actual impact. He advocates for an enhanced form of citizenship that encourages more interaction between citizens and the government. Also see Albert J. Meijer et al., “Open Government: Connecting Vision and Voice,” International Review of Administrative Sciences 78, no. 1 (2012): 10-11, supra note 4. ↩︎

The majority of studies on public administrative communication focus on presidential communication strategies, public relations, government communication with the media, propaganda studies, and the interplay between government, press and public opinions. ↩︎

Convention Citoyenne CESE, “Rapport de la Convention Citoyenne sur la fin de vie,” 2023, accessed January 23, 2024, https://conventioncitoyennesurlafindevie.lecese.fr/sites/cfv/files/Conventioncitoyenne_findevie_Rapportfinal.pdf. ↩︎

Mike Cummings, “Yale Scholar Helps Steer French Citizens’ Assembly on Euthanasia,” YaleNews, May 3, 2023, https://news.yale.edu/2023/05/03/yale-scholar-helps-steer-french-citizens-assembly-euthanasia. ↩︎

Brian Christopher Jones and Yen Tu Su, “Confrontational Contestation and Democratic Compromise: The Sunflower Movement and Its Aftermath,” Hong Kong Law Journal 45 (2015): 193, 202. ↩︎

Ming-sho Ho, “Occupy Congress in Taiwan: Political Opportunity, Threat, and the Sunflower Movement,” Journal of East Asian Studies 15 (2015): 1, 69, 85; and Ian Rowen, “Inside Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement: Twenty-Four Days in a Student-Occupied Parliament, and the Future of the Region,” The Journal of Asian Studies 74, no. 1 (2015): 5, 14. ↩︎

Ian Rowen, supra note 10, at 15; and Panayiota Tsatsou, “Social Media and Informal Organisation of Citizen Activism: Lessons from the Use of Facebook in the Sunflower Movement,” Social Media + Society (2018): 1-12. ↩︎

Public Digital Innovation Space, “Home,” accessed January 23, 2024, https://pdis.nat.gov.tw/en/. ↩︎

“Discuss the PDIS Open Government Liaison Mechanism with Director of Asset Management,” Public Digital Innovation Space, November 25, 2016, visited on August 20, 2023, https://sayit.pdis.nat.gov.tw/2016-11-25-與資管處長討論-pdis-開放政府連絡機制. ↩︎

The survey report of the JOIN Platform in 2020, NDC. https://ws.ndc.gov.tw/Download.ashx?u=LzAwMS9hZG1pbmlzdHJhdG9yLzEwL2NrZmlsZS9lNDA4Y2Q0Yy1iNjViLTRhMzUtYWRlNS03MWU1NzJiMDhmOTYucGRm&n=MTA55bm05YWs5YWx5pS%2F562W57ay6Lev5Y%2BD6IiH5bmz6Ie65YWs5rCR5Y%2BD6IiH5oOF5b2i6Kq%2F5p%2Bl5aCx5ZGKKOWFrOWRiueJiCkucGRm&icon=.pdf ↩︎

“ORID – strategic questioning that gets you to a decision,” PacificEdge, August 28, 2018, accessed on August 20, 2023, https://pacific-edge.info/2018/08/28/orid/. ↩︎

“Users Journeys,” Service Design Toolkit, accessed on January 23, 2024, https://www.servicedesigntoolkit.org/assets2013/posters/EN/S6-users-journeys-A0.pdf. ↩︎

“Idea Development Sheet,” UK Government, accessed on January 23, 2024, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5791ff0ce5274a0da9000140/Idea_development_sheet_.pdf. ↩︎

“Tax Declaration System Satisfaction Exceeds 90%,” CSR Tradevan, accessed on January 23, 2024, https://csr.tradevan.com.tw/news20200723/. ↩︎

環保署公告「一次用塑膠吸管限制使用對象及實施方式」(Environmental Protection Agency Announcement “Restricted Use of Single-Use Plastic Straws and Implementation Methods”), https://enews.moenv.gov.tw/page/3b3c62c78849f32f/dc192b58-cbbf-4c34-8ac0-5cd7ce5ce321 ↩︎